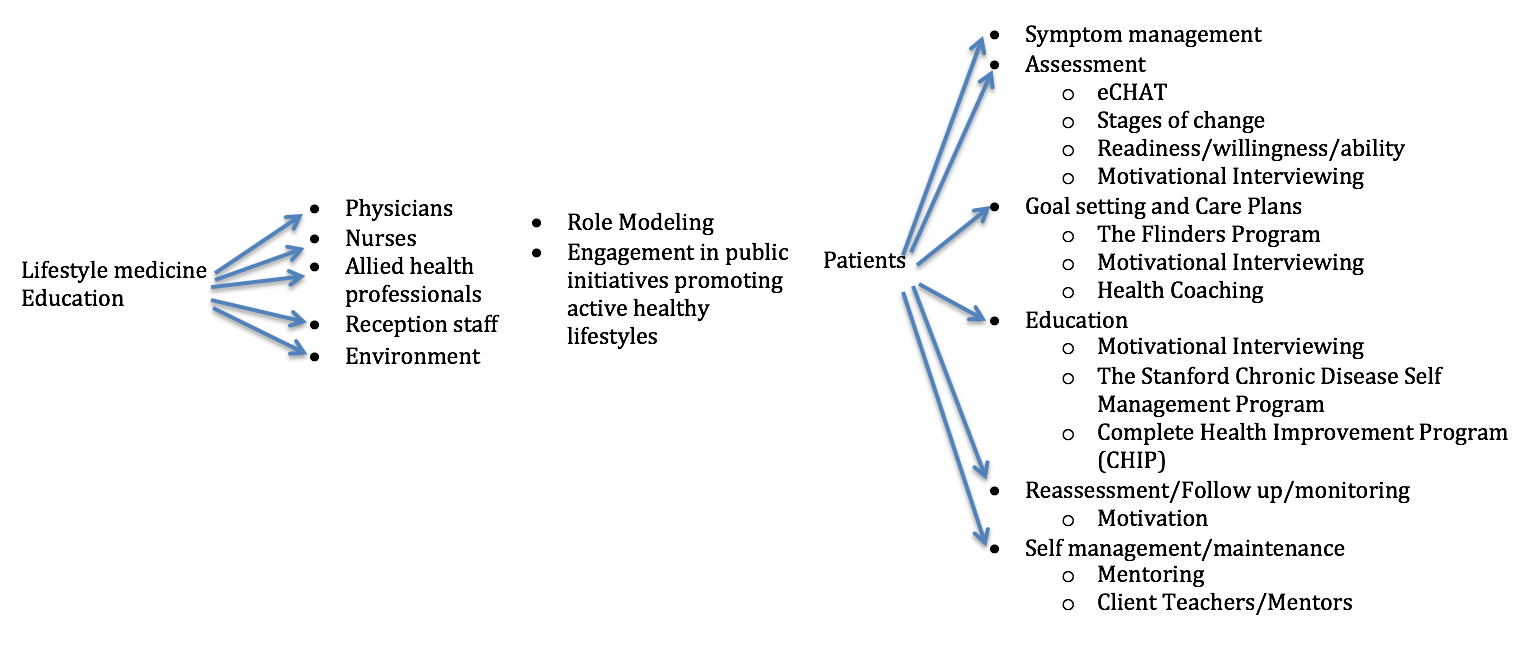

Lifestyle Medicine and professional practice

Most current research identified that diseases of lifestyle are the most prevalent in our society in recent years; much needs to be done to stem the flow of consequences from this generation’s current lifestyle and protect the next generation. The most trusted individuals in the health equation are doctors and nurses1. Effectively using this broad base of professionals to educate and motivate change in clients will be important in promoting change. The health crisis currently being seen across the globe is multifaceted and therefore requires an arsenal of tools to be used by clinicians to address the issues2. How this may be achieved at the practice level is the subject of this paper.

Clinician knowledge

An initial tool in confronting lifestyle change is to ensure that all practice clinicians and employees are educated and knowledgeable in Lifestyle Medicine. Doctors are traditionally trained to treat symptoms and risk factors, which is important, however searching deeper to treat the cause of disease is much more effective3. Teaching and motivating all clinicians and employees in a practice to embrace lifestyle medicine and be consistent in messages to the clients will enhance the treatment effect.

- Encouraging staff to engage in formal training using incentives and allocating time may facilitate formal education.

- Formal education is available from numerous institutions both in Australia and overseas with many courses accessed online.

- Advertising and encouraging all staff to attend conferences and seminars for lifestyle medicine will be important with or without formal education.

Clinician practice – role modeling

Information is everywhere, any person anywhere can access information about any subject they wish to investigate. Clients need a leader, a person they trust to guide them toward healthy choices. Clinicians need to ‘walk the walk’ and be seen to be doing so. While most evidence is focused on client adherence generated by the mutual collaboration and client satisfaction4 using the influence principle of liking from the work by Cialdini5 clients can relate to clinicians who are also actively participating in positive lifestyle practices.

Engagement in public initiatives promoting active healthy lifestyles

The environment has a large impact on health risks and client compliance6-8. Doctors and nurses being involved in the promotion and support of positive pubic initiatives increases their authority5. This may also increase the effectiveness of initiatives due to the trust the public places in medical professionals1.

Screening and assessment

The ultimate goal of any treatment, from screening and assessment to intervention is for the client to achieve intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy9-11. Screening clients with a lifestyle medicine tool such as a questionnaire to assess for risks, current knowledge and readiness to change will identify the issues most relevant to the client. Prior to any interventions symptoms may need to be managed in an appropriate medical manner as clients may have difficulty learning and making lifestyle changes if their symptoms are not managed well. All clients attending a family practice would benefit from completing a simple Lifestyle assessment questionnaire. A tool such as eCHAT12 developed and tested in New Zealand may be useful. This simple questionnaire completed on a tablet while clients wait to see the doctor incorporates results into the electronic health records of the clinic and may be a useful starting point for clients to think about their lifestyle choices. Using this initial assessment the doctor or nurse can then proceed with further more invasive assessments. As part of this questionnaire the clients also identify their desire for ‘help’ in the items covered. Other assessments to be completed by the doctor or nurse may be:

- Fitness – using the 4S testing13

- Diet – using the Australian Healthy Eating Guidelines14

- Baseline pathology and clinical measurements – blood pressure and pulse, cholesterol, glucose and any other relevant pathology, weight and waist circumference.

Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing is a successful tool to assess the client’s readiness, willingness (importance) and confidence (ability) to change lifestyle behaviours13,15. If the eCHAT tool above is used the clinician will have an insight into this information, however these points can be assessed with brief questioning during the consultation to determine future interventions for the client.

Goal setting and care plans

When the readiness, importance and ability of the client has been established, goal setting tools or models such as the Flinders Program16 will be useful to formalise the clients intention. The Flinders Program include medical investigations, self-management tasks and education, any allied health and community services to be accessed by the client.

Information on a self-management care plan should include:

- The identified issues, including the main problem

- Agreed goals – What the client wishes to achieve

- Agreed interventions – What needs to be done and who is involved in doing it.

- A sign off by both the client and health professional

- Review dates.

This information can be used with The Chronic Disease Management and Team Care Arrangements available through Medicare and the Australian Government17.

Health coaching

Health Coaching is an intervention with a coach guiding the client through health changes with the client actively participating using self-identified health goals. The essence of coaching is a strength-based approach where the client is considered the expert in his or her own health and the medical professional/coach is the support18,19. Health coaching is done with the client not to the client20. Coaching places the client in control of their health and managing their medical condition with the support of the medical professionals. Health coaching utilizes the knowledge and skills of the health practitioners with principles from health psychology and behavioural medicine, along with the skills and techniques of performance and development coaching20.

Education

When client goals are established and plan agreed upon the clinician is able to refer or initiate education. This can be group education sessions scheduled regularly in the practice or individual education scheduled as identified. Group education sessions should be accessible by all clients in the practice who are interested in increasing knowledge about lifestyle risk factors, thereby increasing the influence and preventative nature of this intervention.

Several well-established, researched programs are available to be used by the practice. Using information about the client’s, including their needs and problems can inform the practice about the appropriate program to use.

Stanford School of Medicine offer guidelines and resources for ‘The Chronic Disease Self-Management Program’ (Better Health, Better Choices Workshop)21. This is a six-week community education program facilitated by two trained leaders one of whom can be a health professional if desired but at least one facilitator has a chronic disease. Participants are supplied with a text and relaxation CD to support learning and participation. Numerous subjects are covered including, techniques for dealing with fatigue, pain, frustration and isolation, exercise, medications, communication, nutrition, decision making and evaluating new treatments. Classes are effective as the material encourages mutual support and sharing to engage participants thus increasing their self-efficacy. This program is designed to complement established disease specific programs such as cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation programs. Studies reveal this program improves self-efficacy and decreases hospital presentations22,23.

The Lifestyle Medicine Institute offers an 18-session program that can be facilitated by health professionals as well as non-health professions in a community or clinic setting24. The Complete Health Improvement Program (CHIP) uses regularly updated video education, facilitated discussion and local presentations including cooking demonstrations. Participants are supplied with a workbook, recipe book, text, water bottle and pedometer to support learning and activity. Studies show the effectiveness of this program in reducing lifestyle risk factors and changing participant behaviours25,26.

These programs are a sample of researchable lifestyle programs available. Knowing the client profile and available facilities and staff will guide clinicians in choosing the most appropriate program to be incorporated into the practice or clients can be referred to a local chapter of an established program.

Promoting health habits can also be achieved passively by having health promoting reading material in waiting area and displaying health promoting activities and events throughout all areas of the practice.

Reassessment

Regular assessment, either by the client or in the practice, is import to assist the client to maintain health changes as identified in the weight loss examples of the National Weight Loss Registry27,28. The majority of people are motivated by success, if this can be demonstrated by regular follow-up assessment client’s will be motivated to sustain lifestyle changes. When reassessment is done regularly, small changes positively or negatively can be identified and new goals discussed and achievements celebrated.

Self-management/client teaching

The ultimate goal of all lifestyle interventions is self-management13. Clients need to take responsibility for their own health with the support and encouragement of clinicians. Supporting clients to become teachers, facilitators or mentors as in the programs discussed above or in less formal settings such as support groups or friendships will reinforce the learning and maintenance experience.

A menu of options available for the health professional is an important tool. Choosing to incorporate one program may not suit all clients in a practice; using a menu of choices the clinician is able to refer their clients to a program or clinician more suited to his or her needs. Identifying risk factors and client’s ready to change or ready to enquire about change is the most important first step in supporting lifestyle. A practice focused on addressing lifestyle change prior to seeing clients and actively screening all clients in the practice increases the probability that clients will be identified and well supported.

- Australia RD. Professions we Trust Austalia2013 [cited 2014 15/5/14]. Available from: http://www.readersdigest.com.au/most-trusted-professions-2013.

- Candib LM. Obesity and diabetes in vulnerable populations: reflection on proximal and distal causes. Annals of family medicine. 2007 Nov-Dec;5(6):547-56. PubMed PMID: 18025493. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2094018.

- Mark A. Hyman MD DOM, Michael Roizen MD. Lifestyle Medicine: Treating the causes of disease. Alternative Therapies in Health & Medicine. 2009;15(6):12-4.

- Leslie R Martin SLW, Kelly B Haskard & M Robin DiMatteo. The challenge of patient adherence. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 2005;1(3):189-99. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC1661624.

- Cialdini RB. Influence, Science and Practice. Fifth ed. United States of America: Pearson; 2014. 267 p.

- Carpenter DO. Environmental contaminants as risk factors for developing diabetes. Rev Environ Health. 2008 Jan – March;23(1):59 – 74.

- Brownell K. Toward optimal health: Dr. Kelly Brownell discusses [corrected] the influence of the environment on obesity. Interview by Jodi R. Godfrey. Journal of women’s health. 2008 Apr;17(3):325-30. PubMed PMID: 18328015.

- McAdams CB. The environment and pediatric overweight: a review for nurse practitioners. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2010 Sep;22(9):460-7. PubMed PMID: 20854637.

- Michel Bernier JA. Self-efficacy, outcome, and attrition in a weight-reduction program. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1986;10(3):319-38.

- Shannon Byrne DB, Nancy M. Petry. Predictors of weight loss success. Exercise vs. dietary self-efficacy and treatment attendance. Appetite. 2012 (58):695-8.

- Reeve J. Understanding Motivation and Emotion. Fifth Edition ed. United States of America: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2009. 581 p.

- Felicity Goodyear-Smith CBChB M, FRNZCGP, Jim Warren, PhD, Minja Bojic, Angela Chong, BBus, RGN. eCHAT for LIfestyle and Mental Health Screening in Primary Care. Annals of family medicine. 2013;11(5):460-6.

- Egger G. BA, Rossner S. Life Style Medicine Managing Diseases of Lifestyle in the 21st Century. 2nd ed. Australia: McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd; 2011 2011.

- Government A. Australian Guide for Healthy Eating [16/5/14]. Available from: http://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/guidelines/australian-guide-healthy-eating.

- S. MWRR. Motivational Interviewing – Helping People Change. 3rd ed: The Guilford Press; 2013.

- University F. The Flinders Program Flinders University [16/5/14]. Available from: http://www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/sites/fhbhru/self-management.cfm – CarePlan.

- Health TDo. Chronic Disease Management: Australian Government; 2014. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mbsprimarycare-chronicdiseasemanagement.

- Liddy C, Johnston S, Nash K, Ward N, Irving H. Health coaching in primary care: a feasibility model for diabetes care. BMC family practice. 2014;15:60. PubMed PMID: 24708783. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4021256.

- Mettler EA, Preston HR, Jenkins SM, Lackore KA, Werneburg BL, Larson BG, et al. Motivational improvements for health behavior change from wellness coaching. American journal of health behavior. 2014 Jan;38(1):83-91. PubMed PMID: 24034683.

- Penny Newman RVaAM. Health coaching with long-term conditions. Practice Nursing. 2013;24(7):344-6.

- Medicine SSo. Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (Better Choices, Better Health Workshop) [16/5/14]. Available from: http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/cdsmp.html.

- KATE R. LORIG D, PHILIP RITTER, PHD, ANITA L. STEWART, PHD, DAVID S. SOBEL, MD,, BYRON WILLIAM BROWN J, PHD, ALBERT BANDURA, PHD, VIRGINIA M. GONZALEZ, MPH,, DIANA D. LAURENT M, AND HALSTED R. HOLMAN, MD. Chronic-Disease-Self-Management-Program_-2 Year Health Status and Health Care Utilization Outcomes. Medical Care. 2001;39(11):1217-12223.

- Lorig KRR, DRPH, Sobel, David S., MD, MPH, Ritter, Philip L., PhD, Laurent, Diana, MPH, Hobbs, Mary, MPH. Effect of self management in Chroic disease. Effecitive Clinical Practice. 2001;4(6):256-62.

- Institute LM. CHIP – Complete Health Improvement Program 2013 [18/5/14]. Available from: http://www.chiphealth.com/.

- Lillian Kent DM, Trevor Hurlow, Paul Rankin, Althea Hanna, Hans Diehl. Long-term effectiveness of the community-based Complete Health Imporvement Program (CHIP) lifestyle intervention: a cohort study. BJM Open. 2013;3(11).

- David Drozek HD, Masato Nakazawa, Tom Kostohryz, Darren Morton, Jay H. Shubrook. Short-term effectiveness of a Lifestyle intervention program. Advances in Preventive Medicine. 2014;2014:1-7.

- Hill RRWaJO. Successful Weight Loss Maintenance. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2001;21:323-41. Pubmed Central PMCID: 11375440.

- Ogden LG, Stroebele N, Wyatt HR, Catenacci VA, Peters JC, Stuht J, et al. Cluster analysis of the national weight control registry to identify distinct subgroups maintaining successful weight loss. Obesity. 2012 Oct;20(10):2039-47. PubMed PMID: 22469954.

This article has been written for the Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine (ASLM) by the documented original author. The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the original author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the ASLM or its Board.