Sarcopenia, Lifestyle Medicine and Interdisciplinary Management

Dr Peter McCann MRes,FASLM, Dr Peter McGlynn PhD,FASLM, Dr Carl Thistlethwayte MChiro,FASLM

Introduction

Sarcopenia is a progressive skeletal muscle disorder characterised by a decline in muscle strength, mass, and physical performance, formally recognised in 2016 as a chronic disease with its own ICD-10 code (M62.84). While traditionally viewed through a geriatric lens, sarcopenia has become increasingly relevant to the fields of physiotherapy, chiropractic, exercise physiology and osteopathy due to its strong association with musculoskeletal dysfunction, frailty, and chronic disease[1].

This condition now demands attention as both a lifestyle-driven and lifestyle-responsive disorder, positioning allied health professionals at the forefront of its prevention and management. Sarcopenia’s systemic consequences extend beyond muscle loss; it reflects a multisystem syndrome of metabolic dysregulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, hormonal decline, inflammation, and physical inactivity[2]. The following discussion will outline the latest understanding of sarcopenia’s pathophysiology, diagnostic advances, and evidence-based interventions, framed within a lifestyle medicine approach to support interdisciplinary, proactive musculoskeletal care.

The Musculoskeletal and Metabolic Interface of Sarcopenia

Skeletal muscle is not only essential for movement and function but also for systemic metabolic homeostasis. Muscle mass is the primary site of postprandial glucose disposal and a key regulator of lipid metabolism. Loss of muscle mass and function, as seen in sarcopenia, is therefore closely linked with metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease[3]. Sarcopenia also increases the risk of osteoporosis, contributing to a vicious cycle of physical decline and loss of independence.

Importantly, skeletal muscle acts as an endocrine organ through the release of myokines such as irisin and interleukin-6, which mediate anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitising effects[4]. Regular contraction-induced myokine secretion plays a crucial role in maintaining whole-body homeostasis. Conversely, sedentary behaviour and sarcopenia lead to myokine deficiency, chronic low-grade systemic inflammation, and functional decline.

Given these complex bidirectional relationships, sarcopenia serves as both a consequence and amplifier of broader chronic disease processes, a concept especially relevant to allied health professionals engaged in physical rehabilitation and prevention.

Prevalence and Clinical Impact in Australia

Globally, sarcopenia affects 10–30% of older adults, with higher rates in those who are hospitalised or institutionalised[5]. Recent meta-analyses suggest the prevalence of severe sarcopenia in community-dwelling populations ranges from 2.2% to 10%, depending on the criteria used[6]. In Australia, the growing ageing population means sarcopenia is increasingly encountered in primary care and rehabilitation settings. It often goes unrecognised due to poor screening uptake and a lack of standardised assessments in clinical practice.

Sarcopenia is independently associated with falls, fractures, functional dependency, cognitive decline and increased mortality risk[7]. Its clinical trajectory also overlaps with common MSK complaints such as chronic back pain, joint stiffness, and reduced mobility, complicating diagnosis unless actively screened.

Updated Diagnostic Frameworks and Screening Tools

The European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2) updated their diagnostic framework in 2019, emphasising low muscle strength as the primary indicator, confirmed by reduced muscle quantity or quality, and categorised by impaired physical performance[1]. This stepwise approach remains the gold standard internationally and is applicable in Australian allied health settings.

Key measures include:

- Grip Strength: <27 kg (men) or <16 kg (women) indicates probable sarcopenia[1].

- Chair Stand Test: >15 seconds for 5 rises is associated with low strength[8].

- Gait Speed: <0.8 m/s reflects poor functional performance and increased fall risk[9].

- Muscle Mass: Ideally measured using Dual-energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA), though validated alternatives like Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) are accessible in many clinical settings.

The SARC-F questionnaire is a validated, rapid self-reported tool assessing strength, walking ability, rising from a chair, stair climbing and falls. It has high specificity and is ideal for screening in busy clinical environments[10].

Recent research has added nuance to diagnosis, recommending inclusion of muscle-specific force (strength per unit mass) to identify functional sarcopenia that may be missed by mass-based assessments alone[11].

Pathophysiology: A Multifactorial Decline

The biological underpinnings of sarcopenia are complex and multifactorial and include:

- Anabolic Resistance: Reduced muscle protein synthesis in response to dietary protein or exercise in older adults[12].

- Age-related poorer digestion: less efficient digestion or unmanaged caloric restriction may predispose older adults to inadequate absorption of protein and amino acids.

- Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Impaired ATP production and increased oxidative stress compromise muscle energetics[2].

- Endocrine Dysregulation: Decreased testosterone, oestrogen, growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) contribute to catabolism[13].

- Inflammaging: Chronic low-grade systemic inflammation, marked by elevated TNF-α and IL-6, promotes muscle breakdown and insulin resistance[14].

- Neuromuscular Degeneration: Denervation and motor unit loss further reduce muscle recruitment and function[15].

Understanding these mechanisms provides a rationale for multidimensional interventions targeting strength, nutrition, inflammation, and lifestyle behaviours.

Lifestyle Medicine and MSK Strategies for Sarcopenia Management

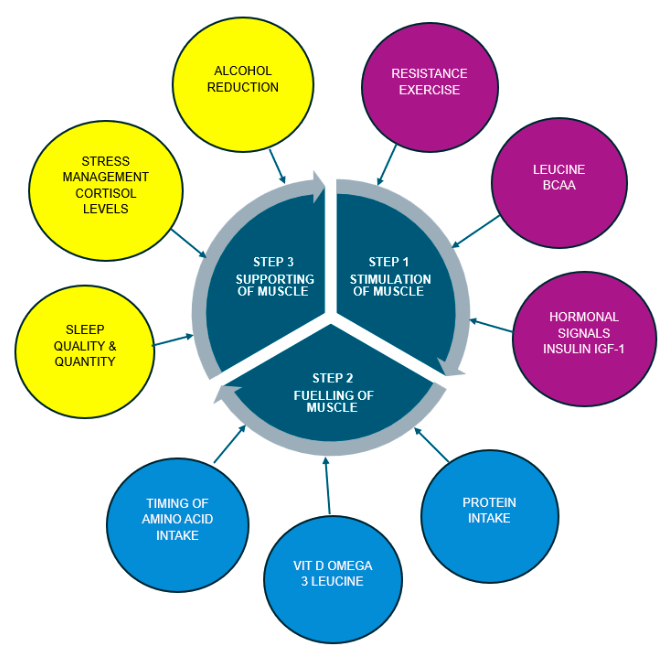

Figure 1: Lifestyle factors that influence muscle protein synthesis

Physical Activity as a cornerstone intervention

Progressive resistance training (PRT) is the most effective strategy to prevent and reverse sarcopenia. It improves muscle mass, strength, balance, and functional capacity even in the very old or frail[16]. A 2022 Cochrane review confirmed that PRT significantly improves mobility and reduces falls in sarcopenic adults across diverse settings[17].

Key principles include:

- Moderate-to-high intensity resistance (70–85% 1RM)

- Two to three sessions per week

- Focus on large muscle groups (e.g. hips, thighs, trunk)

- Progressive overload

Musculoskeletal clinicians well-versed in sarcopenia management such as exercise physiologists, chiropractors, physiotherapists and osteopaths are well placed to prescribe and supervise such programs, tailoring them to individual capabilities and health goals.

Combined programs incorporating balance, flexibility, and aerobic training yield superior outcomes.

Protein intake, nutritional screening and support

Dietary protein is essential to support muscle protein synthesis. Older adults exhibit “anabolic resistance,” requiring higher protein intakes than younger individuals. Current consensus recommends 1.2–1.5 g/kg/day of protein, ideally as part of a balanced diet and distributed across meals to meet protein requirements and support optimal muscle stimulation[18]. When dietary protein intake is inadequate or difficult, evidence suggests that leucine-enriched protein supplementation enhances the anabolic response, particularly when combined with resistance training[19]. Whey protein isolate remains the gold standard for supplementation, due to its high leucine content and rapid digestibility.

Vitamin D repletion is also important, as deficiency is common in older adults and associated with muscle weakness and impaired balance[20]. Moderate daily sun exposure or oral supplementation are valid sources of Vitamin D.

Simple screening tools such as a 3-day food diary, 24-hour diet recall and the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) can identify at-risk individuals at risk due to unmanaged caloric restriction, which may increase the risk of sarcopenia. These tools can guide appropriate and timely referral to dietitians.

Systemic Inflammation, Gut-Muscle Axis and Sleep

Emerging research highlights the role of the gut-muscle axis, where microbiome composition and gut permeability influence systemic chronic inflammation and muscle mass regulation. Exercise and prebiotic/probiotic strategies may support muscle function indirectly through microbial modulation[21].

Sleep quality is another overlooked but important factor. Short sleep duration and poor sleep efficiency are linked with sarcopenia, likely through hormonal and inflammatory pathways[22]. Interventions targeting sleep hygiene, stress reduction, and circadian rhythm support can improve recovery and reduce the risk of sarcopenia.

Manual Therapy and Movement Optimisation

While manual therapies do not directly increase muscle mass, spinal manipulation, mobilisation and soft tissue techniques may support sarcopenia management by:

- Reducing pain and facilitating movement

- Improving posture and proprioception

- Enhancing engagement with physical activity

Systematic reviews support the use of manual therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain and functional restoration, which may facilitate movement and active rehabilitation in older clients[23].

Behavioural Support and Psychosocial Integration

Lifestyle Medicine emphasises behaviour change and self-efficacy. Motivational interviewing, goal setting, and readiness for change assessment are systematic evidence-based strategies that support engagement and adherence [24]. Use of the Lifestyle medicine screening questionnaire, LM-25, (a free resource with ASLM Practitioner Membership), enables clinicians to assess a client’s lifestyle behaviours to explore and co-design behavioural change strategies and health priorities. Sarcopenia assessment and management is best implemented using the 5A’s framework.

Sarcopenia is also influenced by social isolation and depression, which can reduce both physical activity and nutritional intake. Allied health providers can screen for lifestyle factors including psychosocial barriers that may contribute to sarcopenia and then coordinate with GPs or mental health professionals when appropriate.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration and Policy Integration

Allied health professionals with appropriate education and competencies should actively engage in interdisciplinary networks to address sarcopenia holistically. Coordinated care using the Medicare Chronic Disease Management (CDM) plan involving GP’s, geriatricians, exercise physiologists, chiropractors, physiotherapists and, osteopaths ensures continuity and effectiveness and a person-centred approach.

Australia’s National Preventive Health Strategy 2021–2030 emphasises healthy ageing, functional independence, and the role of non-pharmacological interventions, making sarcopenia an ideal target for allied health-led initiatives[25].

Embedding sarcopenia screening and exercise programs in primary care, aged care, and hospital discharge planning represents a systems-level opportunity to reduce disability and healthcare costs.

Conclusion

Sarcopenia is a prevalent and under-recognised condition that intersects directly with the core goals of musculoskeletal and lifestyle medicine. As Australia’s population ages, the role of allied health professionals in screening, preventing and managing sarcopenia will become increasingly critical.

Through evidence-based exercise prescription, nutritional guidance, manual therapy, behavioural support and interdisciplinary collaboration, practitioners can make a significant impact on individual and public health outcomes. Sarcopenia should no longer be considered a passive consequence of ageing it is a modifiable, preventable, and reversible condition when addressed early through lifestyle medicine and rehabilitative care.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31.

- Ticinesi A, Lauretani F, Tana C, et al. Exercise and immune system as modulators of intestinal microbiome: implications for the gut-muscle axis hypothesis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2752.

- Seixas BV, Viana CM, Cunha GRS, et al. Muscle mass and metabolic health: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2023;15(4):928.

- Whitham M, Febbraio MA. The ever-expanding myokinome: discovery challenges and therapeutic implications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(10):719–29.

- Petermann-Rocha F, Balntzi V, Gray SR, et al. Global prevalence of sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13(1):86–99.

- Mayhew AJ, Amog K, Phillips S, et al. The prevalence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(5):719–27.

- Dodds RM, Granic A, Robinson SM, et al. Sarcopenia and falls in older adults: findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3):e052591.

- Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Beam WC. A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70(2):113–9.

- Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Penninx BW, et al. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(10):1675–80.

- Malmstrom TK, Morley JE. SARC-F: a simple questionnaire to diagnose sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):531–2.

- Kirk B, Cawthon PM, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, et al. Muscle-specific force as a diagnostic criterion for sarcopenia: analysis from the Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia. Age Ageing. 2024;53(3):afae040.

- D’Souza RF, Zeng N, Wahlin-Larsson B, et al. Muscle protein synthesis and anabolic resistance in ageing. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2021;24(3):243–50.

- Giudice V, Barone F, Petta S, et al. Muscle and bone endocrine functions: pathophysiological role and cross-talk. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab. 2020;18(1):1–12.

- Gielen E, O’Neill TW, Pye SR, et al. Endocrine determinants of muscle mass and strength. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45(2):251–63.

- Nishikawa Y, Kanda Y, Kondo S, et al. Role of neuromuscular junctions in age-related sarcopenia. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(8):3706.

- Peterson MD, Sen A, Gordon PM. Resistance exercise for muscular strength in older adults: a meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;9(3):226–37.

- Beckwée D, Delaere A, Aelbrecht S, et al. Exercise interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56(13):773–8.

- Bauer J, Biolo G, Cederholm T, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):542–59.

- Kim HK, Suzuki T, Saito K, et al. Effects of exercise and amino acid supplementation on body composition in elderly Japanese women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(1):16–23.

- Bislev LS, Langagergaard RO, Rolighed L, et al. Effects of vitamin D on muscle strength, mass and physical performance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(3):e931–44.

- Ni Lochlainn M, Bowyer RCE, Steves CJ. Dietary protein and muscle in aging people: the influence of the gut microbiome. Nutrients. 2018;10(7):929.

- Yoshiko A, Kaneko M, et al. Sleep disturbance and sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2023;12(1):123.

- Coulter ID, Crawford C, Hurwitz EL, et al. Manipulation and mobilization for chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J. 2018;18(5):866–79.

- O’Halloran PD, Shields N, Blackstock F, et al. Motivational interviewing for physical activity in chronic health conditions. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(12):1159–71.

- Australian Government Department of Health. National Preventive Health Strategy 2021–2030. Canberra: DoH; 2021.

Join ASLM’s Musculoskeletal Health Community of Practice (MSK CoP)

Are you passionate about musculoskeletal health and ready to collaborate with like-minded professionals? ASLM is reinvigorating its Musculoskeletal Health Community of Practice (MSK CoP) and inviting expressions of interest from ASLM Members and ASLM Accreditation in Lifestyle Medicine (AALM) candidates.

The MSK CoP exists to promote musculoskeletal health through evidence-based lifestyle interventions, research, education, and advocacy. Members contribute to shaping the group’s scope, structure, and direction – through regular meetings, knowledge sharing, collaborative projects, and strategic planning.

Be part of a collaborative, forward-thinking group helping to shape the future of MSK care.

- Connect with Dr Peter McCann, Dr Peter McGlynn, or Dr Carl Thistlethwayte directly via the links below

- Join the Musculoskeletal Community of Practice Group

- For more information, contact the ASLM Team at info@lifestylemedicine.org.au

Dr Peter McCann

Dr Peter McCann is a Research Master, Chiropractor, Chinese Medicine Practitioner, Naturopath, certified lifestyle medicine professional (IBLM), bone densitometry technologist, and Fellow of both the Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine (ASLM) and the Australasian Institute of Clinical Education (AICE). He developed FlexEze heat wraps — a TGA-registered medical device used in major hospitals and allied health clinics for managing low back pain. Dr McCann is also the national clinical educator for Immuron, an Australian biotech company focused on novel oral immunotherapies. His special interests include sarcopenia, the microbiome, and non-pharmacological interventions for low back pain.

Dr Peter McGlynn

Dr Peter McGlynn is a registered chiropractor currently practising in Melbourne. He holds a PhD in Global Public Health Nutrition, is certified by the International Board of Lifestyle Medicine, and is a Fellow of the Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine (ASLM). His interests include applying lifestyle medicine principles to health promotion, the management of musculoskeletal conditions, and the interprofessional prevention, management and reversal of lifestyle-related chronic diseases. Dr McGlynn also has extensive experience in global disaster response, international community development, and public health education and research in low-income settings, principally in Papua New Guinea.

Dr Carl Thistlethwayte

Dr Carl Thistlethwayte is a Chiropractor, health coach (HCANZA), certified lifestyle medicine professional (IBLM), bone densitometry technologist, and Fellow of both the Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine (ASLM) and the Australasian Institute of Clinical Education (AICE). He practises at Noosa Mind and Body Clinic in Noosaville, QLD, where he utilises DEXA technology for the prevention, diagnosis, and monitoring of metabolic and chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Dr Thistlethwayte collaborates with allied health teams and GPs through Chronic Disease Management programs and case conferences. The clinic also offers exercise physiology, weight management, GLA:D programs, the Onero osteoporosis program, women’s health GP services, and mental health support.