The evidence for change

Be a leader of change

Lifestyle Medicine is a rapidly growing field that brings together people from every discipline in health to provide evidence-based tools and strategies needed to address the growing challenge of chronic mental and physical illness. The very serious challenges we are all facing, often alone, indicate a great need to bring together and support health care practitioners from diverse backgrounds to ensure that lifestyle interventions are embedded as first line treatment for chronic physical and mental illness so we can move towards whole-of-person and whole-of-community wellbeing. The Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine (ASLM) needs your support to grow its membership and help create systemic change in the delivery of healthcare in Australasia and around the world.

The burden of chronic disease is well articulated through statistics from AIHW1 and WHO2 and further research by Ford3:

- Globally, chronic disease accounts for 73% of all deaths and 60% of the burden of disease

- In Australia, chronic diseases account for 85% of the burden of disease

- ~50% of Australians have at least one chronic disease, with 25% having at least two chronic diseases

- 36% of Australians aged over 70yrs are using 5 or more drugs

- Up to 3 million Australians over the age of 25 years will have diabetes by 2025, with 5% of Australians currently diagnosed with diabetes and 15% with pre-diabetes

- Anti-depressant prescribing has doubled over the 10 years pre-COVID, including to ~100,000 children

Lao Tzu once said, “If you don’t change direction, you may end up where you are headed”. And these statistics in the context of the challenges we face in health and society paint a truly frightening picture that needs leadership and solutions. But despite the scale of this challenge, the evidence tells us that Lifestyle Medicine provides some of the necessary principles and practices to address them in the short and long term.

“Lifestyle as medicine has the potential to prevent up to 80% of chronic disease. No other medicine can match that4.” (Dr David Katz)

Research demonstrates how lifestyle changes can: lower the risk of diabetes by 93%, lower the risk of heart attack by 81%, lower the risk of stroke by 50% and lower the risk of cancer by 36%3.

In addition, the following research reinforces the impact of lifestyle interventions:

- 32% of patients with moderate-to-severe major depression disorder remit with a Modi-Mediterranean diet (vs 8% of control)5

- A meta-analysis of 45,000 participants demonstrated that dietary interventions significantly reduced depression and anxiety symptoms6

- A 2018 study by Lean et al 7 into Type 2 Diabetes shows 46% remission in 12 months for patients if diagnosed in past 6 years, with 80% achieving remission if they lost more than 15kgs

- The 2020 Lancet Commission8 on dementia prevention, intervention and care indicated that 40% of dementias could be delayed or prevented with lifestyle and socio-environmental modification that requires both public health programmes and individually tailored interventions.

- The Health and Wellness Coaching (HWC) Compendium9 provided an analysis of the “substantial evidence for a clinical intervention yielding a positive impact on the chronic, often lifestyle-related diseases, scourging our modern health care system”

- Sforzo et al.9 concluded when reviewing the impact of HWC on treatment of hypertension that perceived quality of care, medication adherence, avoidable hospitalizations, and cost savings as a result of coaching were other outcomes addressed.

The net cost to the Australian Government of investing in 54 preventative health interventions that have been found to be cost-effective within the Australian context would be $4.5 billion, which is just 2% of the total health expenditure in 2017–201810. Specifically, In the economic analysis of the SMILES trial which reviewed the impact of diet on moderate-severe major depression, the overall healthcare costs were $856 lower and average societal costs were $2591 lower for the diet group over the 12 weeks of the trial due to fewer health professional visits, such as to doctors, dentists, and psychologists11. Interestingly, the food costs for this group were estimated at $26 dollars per week lower than what they would have normally been spending on food before they started the trial.

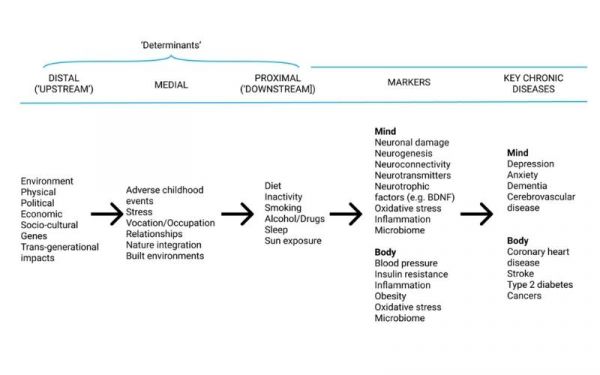

ASLM works with 30 Lifestyle Medicine societies and colleges around the world to bring diverse voices and backgrounds to further the movement of Lifestyle Medicine to support health professionals in the fields of research, clinical practice, public health and beyond so we can provide us all with one of our most effective and much need medicines. Many researchers around the world are helping to add valuable evidence to the case for Lifestyle Medicine. Thanks to their work to date, we have a growing confidence in the crucial role of lifestyle assessments and interventions. But Lifestyle Medicine is far more effective when implemented through new models of care that utilise health coaching, emerging health technologies and empowered health practitioners such as ASLM members who understand the need to treat the whole of person and consider social and environmental determinants of health as well as an individual’s proximal determinants.

Lifestyle Medicine Model of Disease

Adapted from Egger, G., Binns, A., Rossner, S., & Sagner, M. (Eds.). (2017). Lifestyle medicine: Lifestyle, the environment and preventive medicine in health and disease. Academic Press

Lifestyle interventions are recommended as first line treatments in clinical guidelines for some of our most common chronic diseases such as mood disorders12 hypertension, and type 2 diabetes, yet many health professionals report they are not adequately trained or resourced to do this despite their passion and expertise for their art.

“We can’t solve problems using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” (Albert Einstein)

We know that Lifestyle Medicine has a unique ability to impact some of the most pressing health issues of our time and we are committed to seeing it reach its full potential. To that end, ASLM has created the Lifestyle Medicine Innovation Fund (LMIF) to act as a driving force for innovation and capacity building. Contributions to the LMIF fund member innovations and projects to meet the modern challenges to healthcare settings and the public.

If you would like to help fund future innovations in Lifestyle Medicine, you can make a tax-deductible donation here.

If you want to be an active part of that future, and help drive change from the ground-up, please consider joining ASLM as a professional member and be a leader of change.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health 2018: in brief. Canberra: AIHW; 2018.

- World Health Organisation, Chronic diseases and their common risk factors, WHO; 2005.

- Ford, E. S., Bergmann, M. M., Kröger, J., Schienkiewitz, A., Weikert, C., & Boeing, H. (2009). Healthy living is the best revenge: findings from the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition-Potsdam study. Archives of internal medicine, 169(15), 1355–1362. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.237

- Katz, D. L., Frates, E. P., Bonnet, J. P., Gupta, S. K., Vartiainen, E., & Carmona, R. H. (2018). Lifestyle as Medicine: The Case for a True Health Initiative. American journal of health promotion : AJHP, 32(6), 1452–1458. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117117705949

- Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Opie R, Itsiopoulos C, Cotton S, Mohebbi M, Castle D, Dash S, Mihalopoulos C, Chatterton ML, Brazionis L, Dean OM, Hodge AM, Berk M. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Med. 2017 Jan 30;15(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y. Erratum in: BMC Med. 2018 Dec 28;16(1):236. PMID: 28137247; PMCID: PMC5282719.

- Firth J, Marx W, Dash S, Carney R, Teasdale SB, Solmi M, Stubbs B, Schuch FB, Carvalho AF, Jacka F, Sarris J. The Effects of Dietary Improvement on Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Psychosom Med. 2019 Apr;81(3):265-280. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000673. Erratum in: Psychosom Med. 2020 Jun;82(5):536. Erratum in: Psychosom Med. 2021 Feb-Mar 01;83(2):196. PMID: 30720698; PMCID: PMC6455094.

- Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, Brosnahan N, Thom G, McCombie L, Peters C, Zhyzhneuskaya S, Al-Mrabeh A, Hollingsworth KG, Rodrigues AM, Rehackova L, Adamson AJ, Sniehotta FF, Mathers JC, Ross HM, McIlvenna Y, Stefanetti R, Trenell M, Welsh P, Kean S, Ford I, McConnachie A, Sattar N, Taylor R. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2018 Feb 10;391(10120):541-551. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33102-1. Epub 2017 Dec 5. PMID: 29221645.

- Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Brayne C, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C, Costafreda SG, Dias A, Fox N, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Kivimäki M, Larson EB, Ogunniyi A, Orgeta V, Ritchie K, Rockwood K, Sampson EL, Samus Q, Schneider LS, Selbæk G, Teri L, Mukadam N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020 Aug 8;396(10248):413-446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6. Epub 2020 Jul 30. PMID: 32738937; PMCID: PMC7392084.

- Sforzo GA, Kaye MP, Todorova I, Harenberg S, Costello K, Cobus-Kuo L, Faber A, Frates E, Moore M. Compendium of the Health and Wellness Coaching Literature. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2017 May 19;12(6):436-447. doi: 10.1177/1559827617708562. PMID: 30542254; PMCID: PMC6236633.

- Peeters A, Mihalopoulos C, Harper T, Moodie M, Perez J How much to invest in evidence-based, cost-effective prevention?, Insight MJA, 2021, https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2021/29/how-much-to-invest-in-evidence-based-cost-effective-prevention/

- Chatterton ML, Mihalopoulos C, O’Neil A, Itsiopoulos C, Opie R, Castle D, Dash S, Brazionis L, Berk M, Jacka F. Economic evaluation of a dietary intervention for adults with major depression (the “SMILES” trial). BMC Public Health. 2018 May 22;18(1):599. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5504-8. PMID: 29783983; PMCID: PMC5963026.

- Malhi GS, Bell E, Bassett D, Boyce P, Bryant R, Hazell P, Hopwood M, Lyndon B, Mulder R, Porter R, Singh AB, Murray G. The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2021 Jan;55(1):7-117. doi: 10.1177/0004867420979353. PMID: 33353391.