[fusion_builder_container background_parallax=”none” enable_mobile=”no” parallax_speed=”0.3″ background_repeat=”no-repeat” background_position=”left top” video_aspect_ratio=”16:9″ video_mute=”yes” video_loop=”yes” fade=”no” border_size=”0px” padding_top=”20″ padding_bottom=”20″ hundred_percent=”no” equal_height_columns=”no” hide_on_mobile=”no”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ layout=”1_1″ last=”yes” spacing=”yes” center_content=”no” hide_on_mobile=”no” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” background_position=”left top” hover_type=”none” link=”” border_position=”all” border_size=”0px” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” padding_top=”0″ padding_right=”0″ padding_bottom=”0″ padding_left=”0″ margin_top=”” margin_bottom=”” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″ animation_offset=”” class=”” id=”” min_height=””][fusion_text hide_pop_tinymce=””]

SMA resources menu:

- Introduction and requirements

- SMA workshop videos

- SMA webinar videos

- Background to SMAs (this page)

- Considerations before running SMAs

- Preparation for running SMAs 1

- Preparation for running SMAs 2

- Preparation for running SMAs 3

- Running SMAs

- Evaluating SMA performance

- Links and other resources

Background to Shared Medical Appointments

Summary

Although they have been carried out in the US since 1998, Shared Medical Appointments (SMAs) were only introduced into Australia in 2014. In this year the Australian Lifestyle Medicine Association or ALMA (now the Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine) carried out an introductory pilot study of SMAs to test patient and provider satisfaction with such a process. The trial showed that patient satisfaction and desire for SMAs once they had tried these was extremely high.

Although they had initial reservations, mainly based around organisational and financial concerns, providers (doctors, practice nurses) also had a high level of satisfaction from involvement in SMAs. There was particular support from a small trial of SMAs with indigenous men. Unlike the American model however, it was decided that SMAs could be conducted successfully and economically in Australia with a minimum of two staff (a doctor and a Facilitator) and a patient group of from 6-12 people.

The key to success was the Facilitator, and hence a training program was established by ALMA to certify allied health professionals, but mainly practice nurses, to act as Facilitators for (a) general SMAs (b) more specific ‘programmed’ SMAs involving a specialist program or topic (weight control, smoking etc) over an extended period (eg 6 sessions), and (c) Shared Medical ‘Yarn-ups’ (SMYs) for indigenous health issues.

These resources provide materials for training of Facilitators as a generalist SMA Facilitator. Specialist training is conducted separately.

Rationale for Shared Medical Appointments

The provision of health services at the primary care level, by either a doctor or other health professional requires:

- Knowledge

- Skills

- Tools

Knowledge is information about the determinants and causes of disease:

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Nutrition | Excess energy, fat, sugar, salt; malnutrition |

| Activity | Inactive leisure and/or work time; excessive sitting |

| Stress | Burnout; “brown out”; anxiety; depression |

| Techno-pathology | Adverse effects of technology, injury |

| Inadequate Sleep | Sleep time, disorders |

| Environment | Pollution, endocrine disrupting chemicals |

| Meaninglessness | ‘Learned helplessness’ |

| Alienation | From society |

| Loss of culture (identity) | Such as Indigenous or migrant groups |

| Occupation | Shift work, occupational hazards, bullying |

| Drugs, smoking and alcohol | iatragenesis, ‘recreational’ drugs |

| Over (and Under) exposure | Sunlight, skin cancers, vitamin D Deficiencies |

| Relationships | Support, belonging, care |

| Social inequality | Trust, ratio between rich and poor |

Skills involve the techniques or processes which the provider of health care uses to affect a desired action by the patient to improve his or her health.

Tools are products, devices or services, which help the patient become an active collaborator in the patient-provider relationship.

In the past, knowledge has consisted predominantly of information about infectious or acute diseases or injury, the former being associated with external microbiological organisms or ‘germs’. More recently, these problems have decreased as a proportion of total presentations to primary care in favour of chronic diseases with lifestyle or environmental ‘drivers’ (‘causes’ in the case of chronic diseases are more difficult to define).

This has resulted in a change in the requirements for the skills of medical consultations, from the traditional 1:1 approach typically resulting in relatively simple prescriptive advice, to one where ongoing, complex, health management advice is required over an extended period.

Tools are usually centred around modern technologies, which provide feedback to enable an individual to quantify progress in a particular area of lifestyle or behavioural change. They include screening products such as blood pressure cuffs, HbA1c monitors, and portable spirometers, devices like computers and electronic tablets, and services such as SMS messaging and interactive websites.

Unlike the doctors of the past, modern practitioners, to be effective, have found it necessary to retrain in counselling skills like motivational interviewing, self-management, life coaching, behaviour modification etc. Usually however, this is still within the context of a single 1:1 consultation.

With the more complex, chronic diseases of today (metabolic, respiratory, cardiovascular, carcinogenic etc.), this process has several disadvantages, including the following:

- Under the usual medical reimbursement system (designed initially for quick consultations), there is not enough time for managing complex, chronic problems;

- As chronic diseases have limited lifestyle-related drivers, providers are forced to repeat advice (diet, exercise, stress control etc.) ad nauseum to an ever increasing stream of single patients, thus reducing provider satisfaction;

- Time limitations leave patients ‘short-changed’ on advice and unable to question providers on all issues of concern relating to their disease(s).

- Time restriction often leads providers to prescribe expensive, but not necessarily effective prescription medications rather than explore more complex, but potentially more effective behaviour changes with less potentially iatrogenic side effects.

- Providers sometimes offer advice about which they are not fully confident, but because they know the patient will not question it and probably will not act on it, they do not feel pressured to check the facts.

The 1:1 consulting model has been used since time immemorial, almost as a ‘default’ way of operating, and has rarely been questioned. Because doctors have usually been trained in this process only, they have had no reason to want to change or modify it. Yet changes in health status require changes in health management techniques. There are no supportive data in medical literature to suggest the 1:1 consulting process is more effective than any other.

An Alternative Form of ‘Skill’

All of the above has given rise to the need for consideration of a new form of managing chronic disease at the clinical level, which can:

- Take advantage of peer support

- Reduce patient waiting time

- Allow more time with the doctor

- Be less repetitive for the provider

- Utilize the skills of other experienced health professionals

- Provide more opportunity for learning self-management

- Make no unfounded assumptions about patient health literacy

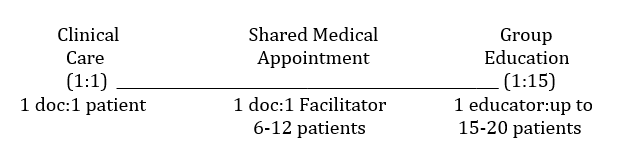

Shared Medical Appointments (SMAs), sometimes known as ‘Group Visits’, offer an alternative to the 1:1 consulting pattern for achieving this. SMAs are defined as “…comprehensive medical visits run in a supportive group setting of consenting patients with similar concerns.” As such an SMA is a comprehensive medical visit, which fits between a single clinical consultation and a group education session (as shown in the diagram below).

[fusion_separator style_type=”single solid” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” sep_color=”” top_margin=”15px” bottom_margin=”20px” border_size=”” icon=”” icon_circle=”” icon_circle_color=”” width=”” alignment=”center”][/fusion_separator]

Where SMAs Fit

SMAs have been run successfully in the US over almost 2 decades, and now in parts of Europe. Until recently, SMAs have never been tested in Australia because it was thought that the Medical Benefits Schedule (Medicare) did not permit these because:

- Visits have to be in a (private) one-on-one situation

- Confidentiality issues preclude discussions of private medical details in front of others

A close scrutiny of the MBS, and discussions with Medicare, show the restrictions are unclear in the MBS relating to (a). As written in the MBS a personal item number (23), which is for less than 20 minutes states that it is for:

“…a service provided in the course of a personal attendance by a single medical practitioner on a single patient on a single occasion.”

As SMAs are conducted in an identical fashion to a 1:1 consultation with individual patients (except with others watching and contributing), this should be no barrier to their use in Australia.

In order to overcome any possible problems with this, the Australian Lifestyle Medicine Association (ALMA) applied in November 2013 to the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) at the behest of the Commonwealth Department of Health for a special item number for SMAs. This was ultimately unsuccessful and at the time of writing (June 2017) there is still no clear guidance from the MBS as to the best way to bill for these consultations. Similarly, there have been no concerns raised at this stage about the use of the Item 23 x number of participants in the group. Item 10997 is also used concurrently x number of participants in the group for the practice nurse. This is how most practitioners are currently billing for SMAs.

Confidentiality (b) can be overcome (as in the US) by confidentiality agreements. Hence, we believe there is no impediment to implementing a billable group visits model for chronic disease in Australia.

What are Shared Medical Appointments?

Shared Medical Appointments are defined as “…a series of individual office visits sequentially attending to each patient’s unique medical needs individually, but in a supportive group setting where all can listen, interact and learn”. (1)

SMAs provide medical care from start to finish – the same as that delivered during routine primary care visits, and often more.

When applied to chronic illness, these can be delivered as comprehensive medical visits (billable at individual rates) focusing on chronic disease, but run in a supportive group setting of consenting patients with similar concerns. The patients sign confidentiality agreements, and 2–4 health professionals are present.

The SMA Team

An SMA team can be made up of as many as 4-5 health professionals depending on the budget available and the topic being discussed. A bigger team might be used where an ‘expert’ in a particular area is brought into a group to discuss a special issue, such as a pharmacist to discuss medications.

Under the US model, the ‘team’ usually consists of a Doctor, a Facilitator (called a ‘Behaviorist’ in the US,) a nurse (to do observations where necessary,) and a Documenter (to keep medical records).

Because of the vagaries of the Australian health care system, a ‘skeleton’ team of a Doctor and a Facilitator are usually sufficient to carry out an SMA. In this case, the Facilitator needs to have good people skills, be well trained in group dynamics, and capable of writing medical records. Practice Nurses are ideally suited for this role and can do this within the financial limitations of the system because they are already on the centre payroll. It is vital that the Doctor not be occupied with keeping medical records so s/he can focus more on individual patient care.

‘Programmed’ (Structured) SMAs

As well as ‘general’ SMAs that may be heterogeneous (e.g. different chronic diseases) or homogeneous (e.g.. all diabetes, or heart disease etc.) SMAs offer a new way to deliver developed programs in specific health areas, where sequential medical consults can add significantly to what otherwise might be simply health educational, group sessions.

Lifestyle-related health areas where this could be particularly relevant include ‘Quitting Smoking’, ‘Weight Loss’, ‘Cardiac Rehabilitation’, ‘Falls Prevention’, etc. In these cases, existing ‘structured’ programs may need little modification to fit the SMA model, because the main benefits of SMAs are medical input in an environment of supportive peers.

Where such programs are available, it is vital that the Facilitator be educated in the area being discussed in order to assist the Doctor, who may not be a specialist in that area. This may require extra training for Facilitators in each of the areas concerned (e.g.. Quitting Smoking, Weight Control etc.) Alternatively, an expert in these areas might be recruited and trained in the techniques of group facilitation.

When should SMAs be used?

SMAs are suitable for a wide variety of health problems, from primary to tertiary care. However, they are likely to be most valuable within secondary care (where risk factors for disease are starting to be seen, but the disease has not yet fully developed).

Areas where published evidence for SMAs exists include:

- Type 2 diabetes (Riley and Marshall, 2010)

- Heart disease (Masley et al., 2001)

- Hypertension (Kawasaki et al., 2007)

- Arthritis (Shojania and Ratzlaff, 2010)

- The Disadvantaged (Clancy et al., 2003)

- Metabolic syndrome sufferers (Greer and Hill, 2011)

- Cancer recoverers (Visser et al., 2011)

- Children and their caregivers (Wall-Haas et al., 2012)

- COPD (Fromer et al., 2010)

- Obesity (Paul-Ebhohimhen and Avenell, 2009)

- The inadequately insured (Clancy et al., 2007)

SMAs may not be as appropriate for such problems as:

- Acute infectious diseases

- Severe mental health issues

- Intimate sexual or other matters

References

- Noffsinger E. The ABCs of Group Visits. Singer, London, 2012.

[/fusion_text][fusion_button link=”/sma-resources-2″ title=”” target=”_self” alignment=”” modal=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” color=”default” button_gradient_top_color=”” button_gradient_bottom_color=”” button_gradient_top_color_hover=”” button_gradient_bottom_color_hover=”” accent_color=”” accent_hover_color=”” type=”” bevel_color=”” border_width=”” size=”” stretch=”default” shape=”” icon=”” icon_position=”left” icon_divider=”no” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”left” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_offset=””]Next section >[/fusion_button][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]